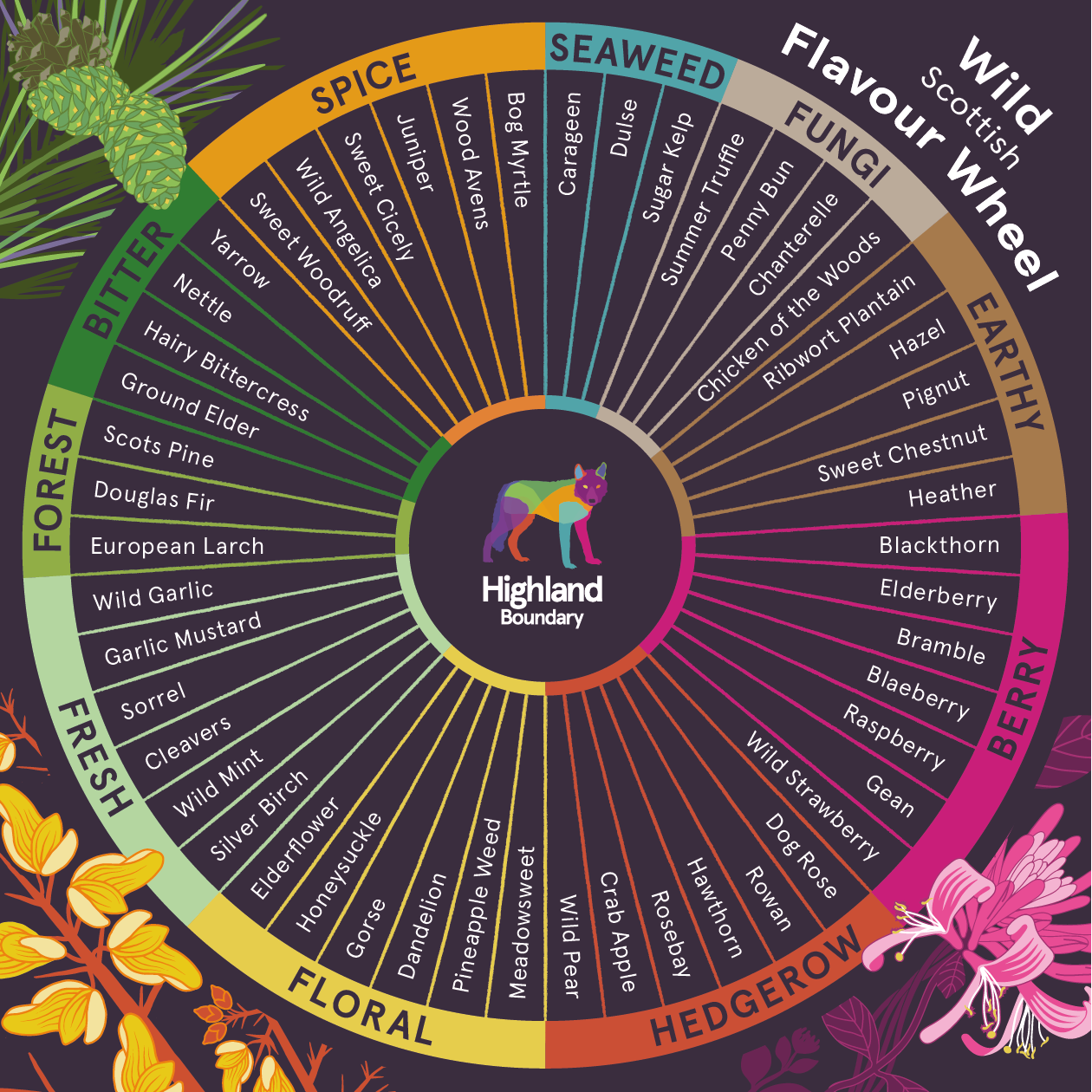

Wild Flavour Wheel

This is currently work in progess and we aim for it to improve and develop over time. We are seeking contributors to provide more content and help take this further as a group effort. In the future we are looking to make this a full interactable online flavour wheel.

To contribute please see the bottom of the page.

How to use

The Wild Scottish Flavour Wheel helps you explore the flavour profiles of species usable in wild foods and drinks. The colour segments are grouped by general taste, each segment is similar in flavour style. Within each segment individual species are broadly arranged by intensity with the transition between segment boundaries closest in similarity. This is always going to be open to debate. We hope this encourages and enables wild flavour enthusiasts to explore the variety and nuances of wild flavours in our landscape.

If you click on a section, a popup will show up with information on the specific flavour. To exit the popup - simply click the x in the top right corner.

We'd love this to be a community collaboration and welcome content input.

Please forage safely and responsibly - pick only an "honourable harvest", leaving the most for nature. Look for information and advice on plant identification and safe use - if you're not sure, don't pick it.

Heather

Name - common name/s and Latin name

- Heather

- Ling

- Scotch Heather

- Calluna Vulgaris

Origin

Heather is native to Europe, particularly widespread across the British Isles, Scandinavia, and parts of western and central Europe. It also grows in parts of Asia Minor and North Africa and has naturalised in North America and New Zealand. It thrives in acidic, nutrient-poor soils, and is especially abundant in moorlands, heathlands, and upland regions. It prefers open, sunny environments and is tolerant of wind, grazing, and poor soil conditions.

Summary

Heather is a low-growing, woody, evergreen shrub that forms dense mats of vegetation across heath and moorland landscapes. It is one of the most iconic and ecologically important plants of upland Britain, where it dominates large expanses of open terrain. Flowering typically occurs from late July into early September, though some varieties may begin earlier or persist longer depending on climate.

Heather plays a critical role in the ecology of moorland, providing shelter and food for birds, insects, and mammals. It is a hardy plant, with small scale-like leaves and abundant clusters of purple to mauve bell-shaped flowers that attract pollinators in late summer.

Where to find Heather

Heather is most commonly found in heathlands, moorlands, coastal headlands, and open pine forests. It prefers acidic, sandy, or peaty soils and is highly tolerant of poor nutrients and exposed, windswept conditions. In the UK, it is a dominant species in the uplands of Scotland, northern England, Wales, and western Ireland. It also occurs in lowland heaths, particularly in southern England and East Anglia.

Look for carpets of low, shrubby growth with fine leaves and vibrant purple flowering spikes in late summer. It often grows alongside gorse, bilberry, and cross-leaved heath.

How to Identify

Heather grows up to 50 cm tall, often forming dense, springy mats. Its leaves are small, scale-like, and arranged in opposite pairs along the stems. They are evergreen and tightly clasp the twig, giving the plant a wiry, fine-textured appearance.

The flowers are small and bell-shaped, clustered in spikes along the upper portions of the stems. They are usually a soft purple or pinkish-mauve but can occasionally be white. Flowers appear from mid to late summer and are a key nectar source for bees and butterflies.

Heather stems are woody at the base, often branching and twisted, with newer growth appearing green and flexible. Older stems turn grey-brown and become tough and brittle.

Sensory Information

Heather has a subtle, earthy scent that becomes more noticeable when flowering. The flowers have a faint honey-like fragrance and are often alive with buzzing insects. The leaves are tough and dry to the touch. The plant has a springy, resilient texture when walked on, forming thick, spongy ground cover in mature heaths.

When dried, the plant maintains its shape and colour well and has historically been used for floral decorations, bedding, and brooms.

How to Use

Heather has a range of traditional uses, both practical and medicinal. While not commonly used in modern cuisine, the flowers are occasionally used to flavour herbal teas or added to honey for a delicate floral taste. Heather honey, produced by bees that forage on the flowers, is highly prized for its rich, aromatic, slightly bitter flavour and thick, jelly-like texture.

In traditional medicine, heather was used as a diuretic, antiseptic, and mild sedative. Infusions of the flowering tops were taken for urinary tract infections, insomnia, or rheumatic complaints. It has also been used in poultices and washes for wounds and skin conditions.

Heather stems were used in the past to make thatch, rope, brooms, baskets, and bedding. In parts of Scotland, dried heather was used to stuff mattresses and insulate walls. Heather was also burned as fuel and mixed with clay and straw to make bricks or building material.

Non food and drink uses

Heather has long been used in craft and construction. Bundles of dried stems made durable brushes and brooms. It was also used in the weaving of heather thatch for roofing in croft houses and rural buildings.

In dyeing, heather produces soft browns, greens, and golds when used with mordants, and its tannin-rich stems were sometimes employed in leather tanning.

Heather is also cultivated in gardens for ornamental purposes and for soil erosion control on slopes and disturbed ground. It supports a rich ecosystem, providing habitat and food for species such as red grouse, golden plovers, and a variety of moths and butterflies. Its role in managed moorlands is central to upland conservation practices.

Cultural References & History

Heather is deeply embedded in Scottish and Celtic culture, where it is seen as a symbol of protection, good luck, and natural beauty. The plant is closely associated with Scottish identity and often appears in Highland folklore, poetry, and traditional dress.

In Scottish tradition, white heather is considered especially lucky and is worn on clothing or carried in bridal bouquets. Purple heather, more common, is still a symbol of admiration and solitude. In Victorian floriography, heather represented admiration or good luck, depending on its colour.

Heather was also important in Norse and Celtic traditions as a sacred plant associated with boundaries, transitions, and liminal spaces. In some legends, heather was said to mark the graves of fairies or be the chosen bloom of wandering spirits.

Mythology

In folklore, heather is often seen as a magical or protective plant. In Scottish legend, it was believed that white heather only grew where blood had not been shed, making it a symbol of peace and purity. Warriors sometimes wore sprigs of heather into battle for luck or carried it as a talisman against harm.

Heather was associated with the Celtic goddess Beira, Queen of Winter, who was said to stride across the hills with heather blooming in her footsteps. In Norse tradition, it was sacred to the goddess Freya and linked to love, fertility, and femininity.

Some beliefs held that burning heather could ward off bad luck or summon spiritual clarity. It was also considered useful in attracting benevolent spirits or ensuring safe passage during travel.

Sweet Chestnut

Name - common name/s and Latin name

- Sweet Chestnut

- Spanish Chestnut

- Castanea Sativa

Origin

Sweet Chestnut is native to the mountainous regions of southern Europe and parts of western Asia. It was likely introduced to Britain by the Romans for its edible nuts and durable timber, and has since become naturalised across southern England and parts of Wales and Ireland. It thrives in warm, temperate climates and prefers acidic, well-drained soils, often found in woodlands, parklands, and along forest edges. It is less common in colder northern regions or heavy clay soils.

Summary

Sweet Chestnut is a large, deciduous tree known for its long, toothed leaves, spiky seed cases, and edible nuts. It can live for many centuries, reaching heights of 20 to 35 metres and developing a broad, domed crown with age. In Britain, the tree flowers in early to mid-summer, producing both male and female flowers on the same tree in long, creamy catkins. The distinctive nuts ripen in autumn, enclosed in sharp, spiny green burrs that split open when mature.

The tree grows rapidly in youth and is widely planted for its valuable timber and ornamental appeal. It is not closely related to the horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum), despite the similar name and nut appearance.

Where to find Sweet Chestnut

Sweet Chestnut trees are commonly found in ancient woodlands, plantations, parks, and along estate boundaries, especially in southern England. They are also grown in coppice systems for wood production. The tree favours acidic or neutral soils, often thriving in sandy or stony conditions. In warmer parts of Europe, it is cultivated extensively for nut production.

Look for tall, spreading trees with spirally ridged bark, long serrated leaves, and spiky green burrs littering the ground in autumn.

How to Identify

Leaves are long and narrow (up to 28 cm), with a glossy green surface and sharply toothed edges. The veins run parallel from the midrib to each tooth. Leaves are arranged alternately along the twigs and turn yellow to brown in autumn.

Flowers appear in June or July. Male flowers form slender, upright catkins, while female flowers are small, green, and sit at the base of some catkins. The tree is wind-pollinated and often strongly scented when in bloom.

Fruits are glossy brown nuts (chestnuts), usually found in groups of two or three inside a green, spiny husk. The husks fall and split open when ripe in October or November.

Bark on young trees is smooth and reddish-brown, becoming deeply fissured and spirally twisted with age. The twisting is a key identifying feature, especially in mature specimens.

Sensory Information

The tree has a warm, earthy scent, especially in flower, when the catkins give off a slightly sweet, musky aroma. The leaves are smooth and leathery with a faint woody fragrance when crushed. The spiny husks are extremely sharp and must be handled carefully.

The nuts are firm and glossy when fresh, with a sweet, nutty taste when roasted. Raw nuts are starchy and slightly bitter but edible. When cooked, they become soft and slightly floury, with a pleasant, mild sweetness. The wood has a light, tannin-rich scent when cut, and the heartwood is pale brown with a smooth, even grain.

How to Use

The nuts are the primary culinary use of Sweet Chestnut. Harvest in mid to late autumn by collecting fallen husks and extracting the nuts. Prickly cases can be opened with boots or gloves. Choose firm, shiny nuts without holes (a sign of weevil infestation).

To prepare, nuts can be roasted, boiled, or baked. The tough outer shell and papery inner skin must be removed, usually after cooking. Roasting brings out their natural sweetness and is the traditional method in European winter markets. Boiled chestnuts are softer and often used in purees or stuffings.

Chestnuts are low in fat and high in starch, making them suitable for flour production. Chestnut flour is naturally sweet and used in breads, pastries, cakes, and pasta. In Italy and France, chestnut-based dishes are part of traditional rural cuisine.

Timber from Sweet Chestnut is highly valued for its strength, durability, and resistance to rot. It is widely used in fencing, furniture, cladding, flooring, and wine casks. When coppiced, it produces long, straight poles ideal for construction and firewood. Coppicing cycles range from 10 to 25 years, depending on end use.

The bark and leaves contain high levels of tannins and were historically used in leather tanning and herbal medicine.

Non food and drink uses

Sweet Chestnut timber is one of the most durable hardwoods grown in the UK, rivaling oak in strength and longevity. It is used in green woodworking, fencing, gate posts, and joinery. It cleaves cleanly and is suitable for rustic crafts and traditional building techniques.

The tree also plays a role in biodiversity, supporting a variety of insects, fungi, and birds. Its flowers attract bees and other pollinators, while the nuts are consumed by wildlife such as deer, wild boar, squirrels, and jays.

Historically, the tree’s tannin-rich bark was boiled for medicinal washes and compresses. Chestnut leaves were used to make infusions for coughs and bronchial ailments in folk remedies.

Cultural References & History

Sweet Chestnut has been cultivated for thousands of years across southern Europe. The Romans are believed to have introduced it to Britain, valuing both the nuts and wood. It became a staple in the diets of poorer rural communities, especially in mountainous regions where grain crops failed.

In parts of France and Italy, chestnuts were once referred to as "the bread of the poor" due to their role as a primary carbohydrate. Chestnut flour sustained communities through winter and famine.

In Britain, Sweet Chestnut has long been used in estate landscaping and forestry. It features in historical coppice systems and parkland designs.

The tree appears in folklore as a symbol of abundance, longevity, and nourishment. In literature, roasted chestnuts are often associated with winter festivities and hearthside gatherings. Traditional songs and poems often mention chestnuts as a symbol of warmth and comfort.

Mythology

Sweet Chestnut does not occupy as prominent a place in myth as oaks or yews but is nonetheless surrounded by folk beliefs. In some traditions, chestnuts were considered protective and associated with prosperity. Carrying a chestnut was thought to bring good fortune and ward off rheumatism.

In Mediterranean cultures, the chestnut tree was sometimes linked to fertility and resilience. In Christian symbolism, the splitting husk revealing the smooth, sweet nut was sometimes used to represent spiritual revelation or hidden virtue.

In modern times, the image of roasting chestnuts over open fires continues to represent nostalgia, comfort, and the warmth of seasonal celebration.

Pignut

Name - common name/s and Latin name

- Pignut

- Earthnut

- Earth Chestnut

- Hog Nut

- Conopodium Majus

Origin

Pignut is native to much of Europe, including the British Isles, and parts of western Asia. It is found in open woodlands, old meadows, hedgerows, and lightly grazed grasslands, preferring light, sandy, or loamy soils. It thrives in nutrient-poor, well-drained environments and is often found in ancient, undisturbed habitats, making it a good indicator of traditional landscapes.

Summary

Pignut is a small, delicate member of the carrot family (Apiaceae), known for its fine, feathery leaves and inconspicuous white flowers. Despite its modest above-ground appearance, it hides a small, edible underground tuber -the “nut”-which is the primary attraction for foragers. This nut has historically been eaten raw or cooked and was once a valued wild snack, especially for children.

Flowering occurs from May to July, and the plant dies back by late Summer. The edible tuber develops slowly and can be harvested throughout the growing season, although it is easiest to find while leaves are still present.

Where to find Pignut

Pignut grows in ancient woodland clearings, old pasture, grassy banks, and hedgerows. It favours well-drained soils and partly shaded environments but will tolerate sun if not too dry. It is widespread in the UK, especially in less intensively managed rural areas.

Look for it in early to midsummer when its delicate leaves and umbels of small white flowers are visible above ground. It is often found among bluebells, wood anemones, and other ancient woodland indicators.

How to Identify

Pignut is a slender plant, growing up to 30 cm tall. Its leaves are finely divided, fern-like, and similar in appearance to wild chervil or cow parsley. The stem is thin and smooth, supporting small, white, five-petalled flowers arranged in compound umbels — typical of the carrot family.

The key feature is the underground tuber, found at the end of a thin root below the surface. This small, round nut (1–2 cm in diameter) is covered in a thin, brown skin and has creamy white flesh inside. The nut is usually buried several centimetres below ground and must be gently unearthed by following the slender root down with fingers or a stick.

Caution is advised when foraging, as many similar-looking members of the carrot family can be toxic (e.g. hemlock or fool’s parsley). Accurate identification is essential before harvesting or consuming.

Sensory Information

The pignut tuber has a sweet, nutty, slightly earthy aroma when freshly dug. Its texture is crisp when raw, similar to a water chestnut or firm radish. The flavour is mild and pleasantly nutty, with a hint of sweetness and a faint taste of hazelnut or coconut.

The leaves are light and feathery to the touch. The flower heads have little to no scent and are often overlooked due to their small size.

How to Use

The edible tuber is the only part of the pignut that is used in food. It can be eaten raw, roasted, or boiled. Traditionally, it was dug up and eaten on the spot, peeled and consumed fresh for its crisp, sweet flavour.

When cooked, the nut becomes softer and slightly sweeter, with a mild chestnut or parsnip-like taste. Roasting enhances its natural sweetness and can be done over hot embers or in an oven. Boiling yields a softer texture but a more muted flavour.

Pignuts can be added to salads raw (after peeling) or incorporated into woodland-style dishes alongside roots, mushrooms, or wild greens. They can also be finely sliced and pan-fried as a delicate garnish or used in savoury custards and wild vegetable soups.

Due to their small size and the labour involved in harvesting, pignuts are not typically used in large quantities but are valued as a forager’s delicacy or seasonal treat.

It is recommended to harvest only sparingly and from areas where the plant is abundant, as digging up the tuber kills the plant. Foraging should be done responsibly, with respect for local conservation guidelines.

Non food and drink uses

Pignut has no significant historical or modern use outside of food and occasional folk reference. It was primarily valued for its edible root, and its delicate appearance made it a familiar sight in traditional countryside settings. The plant contributes to the biodiversity of ancient woodlands and supports insect populations, including hoverflies and solitary bees.

Cultural References & History

Pignuts have been eaten since prehistoric times and were likely a part of the wild plant diet of early humans in Europe. In rural Britain, they were commonly foraged by children who dug them from the forest floor as a snack. Known locally in some areas as “hog nuts” or “earth chestnuts,” they appear in various folk traditions as humble, hidden treasures of the woods.

In historical herbals, the pignut was sometimes praised for its mild diuretic qualities, but it was primarily considered a simple, nourishing wild food rather than a medicinal plant.

Mythology

There is limited mythology directly tied to pignut, but in some folk beliefs, it was considered a playful or mischievous plant - difficult to find, and often said to disappear or “run away” underground if not dug carefully. Its hidden, nut-like root contributed to the idea of secret woodland bounty, and its association with pigs (who also root for them) gave rise to stories of animals leading people to forest riches.

Hazel

Name - common name/s and Latin name

- Hazel

- Common Hazel

- European Hazel

- Corylus Avellana

Origin

Hazel is native to Europe and western Asia, particularly widespread in the British Isles, temperate Europe, and parts of western Russia. It thrives in temperate, deciduous woodlands, hedgerows, forest edges, and mixed scrubland. As a pioneer species, Hazel often establishes quickly in cleared or disturbed areas, contributing to early woodland succession. It prefers well-drained soils and partial shade but can tolerate a range of conditions.

Summary

Hazel is a fast-growing, multi-stemmed deciduous shrub or small tree, typically reaching 3 to 8 meters in height. It is one of the most ecologically and culturally significant woodland species in Europe. Hazel is often found in coppiced woodlands, where it is traditionally managed for its long, flexible poles. It is also valued for its edible nuts, commonly known as hazelnuts or cobnuts.

Flowering occurs very early in the year, often from January to March, making it one of the first signs of spring. Male catkins release yellow pollen, while tiny female flowers, resembling small crimson tufts, appear separately on the same plant. Nuts typically ripen from late August into October, depending on climate and conditions.

Where to find Hazel

Hazel grows widely in ancient woodlands, hedgerows, forest margins, and scrublands. It prefers moist, fertile, and well-drained soils but tolerates chalky or slightly acidic conditions. It can be found throughout the UK and much of Europe, often forming the understorey of oak or ash-dominated woods. Hazel is commonly coppiced in traditional woodland management systems, especially in southern England.

Look for multi-stemmed shrubs with a spreading habit, smooth grey-brown bark, and distinctive catkins in late winter. It often forms dense thickets or is interwoven in hedgerows.

How to Identify

Leaves are rounded to oval with a pointed tip, double-serrated edges, and a softly hairy texture. They grow alternately on the twigs and turn yellow before falling in autumn.

In late winter and early spring, male catkins appear as long yellowish-green tassels, 2–8 cm long, dangling in clusters. The much smaller female flowers are bud-like with protruding red styles, usually visible upon close inspection near the leaf buds.

Hazel bark is smooth and brown to grey, developing horizontal lenticels and peeling in patches with age. Young stems are flexible and light brown with fine hairs. Hazel typically grows as a bushy shrub with multiple trunks rather than a single central stem.

The fruit is a nut (hazelnut or cobnut), encased in a leafy husk that often extends beyond the nut. Nuts ripen in late summer to early autumn and are eagerly eaten by wildlife.

Sensory Information

Hazel leaves are soft and slightly fuzzy when young, with a mild green scent when crushed. The catkins release clouds of yellow pollen when disturbed and have a dry, papery texture. The nuts have a hard outer shell and, when cracked, reveal a creamy, aromatic kernel with a rich, slightly sweet taste.

The wood is smooth, pale, and has a faint woody scent when freshly cut. It is springy and flexible, making it ideal for crafting, hurdles, and fencing.

How to Use

Hazel has a wide range of uses, both traditional and modern.

The nuts are edible and highly nutritious, rich in fats, protein, and vitamins. They can be eaten raw, roasted, ground into flour, or pressed for oil. Harvest in late Summer or early Autumn, collecting before squirrels or birds get to them. Ripe nuts fall easily from the husk when the tree is shaken.

Leaves and catkins are not typically consumed but have been used in herbal infusions historically. Hazel bark and leaves were once used for wound-healing compresses and poultices in folk medicine.

Hazel wood is prized for its flexibility and strength. It has traditionally been used for wattle fencing, walking sticks, tool handles, thatching spars, baskets, and firewood. It is ideal for coppicing, producing new straight shoots every 7 to 10 years.

Hazel rods have long been used in the practice of divining or dowsing for water, minerals, or lost objects. Forked hazel twigs are especially favored for this purpose in folk tradition.

Non food and drink uses

Hazel’s pliable wood has been used for centuries in construction and rural crafts. Coppiced hazel is a sustainable source of renewable wood. It provides excellent materials for hurdles, wattles, pea sticks, and charcoal.

Hazel rods were traditionally used in making sheep hurdles and are still used in some living fencing and conservation practices today.

Hazel is also planted for erosion control and hedgerow restoration. It plays a key role in biodiversity, offering shelter and food for many species, including dormice, jays, woodpeckers, and butterflies like the rare hazel dormouse and the large emerald moth.

Cultural References & History

Hazel has deep roots in European folklore and myth. In Celtic traditions, it is a sacred tree associated with wisdom, inspiration, and poetic knowledge. The hazel tree appears in the ancient Irish tale of the “Salmon of Knowledge,” where the fish gains wisdom by eating hazelnuts that fell into a sacred pool from hazel trees.

In Norse mythology, hazel was associated with Thor and protection. Hazel wands were believed to guard against evil spirits and were used in rituals and magic. In British folk customs, hazel rods were used to mark property boundaries or were planted as charms.

In the medieval period, hazelnuts were symbols of fertility and used in wedding rituals. Hazel was also used in divination, particularly for finding underground water sources.

Mythology

Hazel is strongly linked with myth and magic across many European traditions. In Druidic lore, hazel was one of the nine sacred trees burned in Beltane fires. It was said to grant insight, poetic skill, and mystical vision. The tree’s association with inspiration led to its inclusion in early bardic training and ritual.

Hazel rods have long been used as dowsing tools for locating water or treasure. This practice, still used today in some rural traditions, was believed to rely on the sensitivity of the hazel’s spirit to hidden forces underground.

The sacred well of wisdom in Celtic myth was surrounded by nine hazel trees, whose nuts bestowed divine knowledge when consumed by the Salmon of Knowledge. Eating hazelnuts, therefore, symbolized the gaining of insight, clarity, and sacred truth.

Ribwort Plantain

Name - common name/s and Latin name

- Ribwort Plantain

- Narrowleaf Plantain

- Ribgrass

- English Plantain

- Soldier's Herb

- Lamb's Tongue

- Plantago Lacneolata

Origin

Ribwort Plantain is native to Europe and parts of Western Asia, but it has naturalized widely across North America, Australia, New Zealand, and temperate regions worldwide. It thrives in grasslands, roadsides, gardens, and disturbed ground. Highly tolerant of trampling, poor soil, and dry conditions, it is one of the most widespread wild plants in the Northern Hemisphere.

Summary

Ribwort Plantain is a hardy, perennial herb commonly found in fields, footpaths, and meadows. It grows in a low rosette and produces tall, wirey stalks topped with dense cylindrical flower heads from early Spring into late Autumn. The leaves are long, narrow, and distinctly ribbed, giving rise to the name "ribwort." Flowering typically occurs from April to October, though leaves can be found year-round in milder climates.

It is ecologically valuable as a food source for pollinators and butterfly larvae. Traditionally valued in herbal medicine, it is also edible and occasionally used in wild foraging.

Where to find Ribwort Plantain

Look for Ribwort Plantain in open, grassy areas such as meadows, lawns, pastureland, roadside verges, and disturbed soils. It prefers sun but tolerates partial shade and is especially common in compacted or grazed soils. Found growing in low rosettes with upright flowering stems rising up to 50 cm.

How to Identify

Ribwort Plantain grows from a basal rosette with long, lance-shaped leaves measuring up to 30 cm in length. Leaves are deeply veined with 3 to 7 prominent ribs running from base to tip. The leaf margins are smooth or finely toothed, and the surface may be slightly hairy.

The flower stalks are thin and grooved, reaching up to half a meter tall. The flowering head is a tight brown spike composed of many tiny flowers. During bloom, these flowers produce delicate white stamens that form a halo-like fringe around the head. After flowering, the plant produces small, brown seed capsules.

The root system consists of a shallow fibrous network with a small taproot.

Sensory Information

The leaves are slightly astringent and bitter, with a chewy texture that becomes stringy in older specimens. When crushed, the leaves have a mild, earthy scent. The flower stalks are dry and fibrous. Young leaves are more tender and palatable, especially when steamed or cooked. Texture is leathery, especially in older plants. The flowering head feels bristly and firm.

How to Use

Young leaves can be harvested in Spring and early Summer and used raw in salads or cooked as a leafy green. Due to their fibrous nature, cooking is recommended. Ribwort can be added to soups, stews, and stir-fries as a nutritious wild green.

Leaves can be dried and stored for making herbal tea, traditionally used to treat coughs, sore throats, and mild bronchial conditions. The seeds are edible and high in mucilage, sometimes used similarly to psyllium to aid digestion or regulate bowel movements.

For wound care, fresh leaves can be crushed or chewed and applied directly to the skin to help soothe insect bites, minor cuts, burns, or inflammation. This method was commonly used in folk medicine and by field medics in the past.

To harvest, pick young, undamaged leaves from clean, unsprayed areas. Leaves can be dried or used fresh. Flower heads can also be collected for medicinal or seed use.

Non food and drink uses

The plant's mucilaginous properties make it useful in soothing skin treatments and salves. It has been used in natural cosmetics and herbal compresses for centuries. The tough fibers in the leaves have occasionally been experimented with in cordage. Historically, fresh leaves were used as makeshift dressings on the battlefield.

Cultural References & History

Ribwort Plantain is one of the most ancient and widely used medicinal herbs in European tradition. It was one of the nine sacred herbs listed in the Anglo-Saxon "Nine Herbs Charm," a tenth-century healing incantation. The name "Soldier’s Herb" refers to its use in staunching wounds and reducing swelling during wartime.

The plant was mentioned in several historical herbals and was commonly used in medieval apothecaries. Its resilience and low-growing habit made it a symbol of humility and perseverance. The distinctive flower heads were also used by children in folk games, often flicked from their stalks at each other in mock battles.

Mythology

While Ribwort Plantain does not feature heavily in specific mythologies, it is steeped in folklore. In rural Europe, it was believed to have protective qualities and was carried to ward off illness or bad luck. The Anglo-Saxons associated it with healing magic, and it was said that the plant could neutralize poisons and snake venom if properly prepared.

Some believed that placing the leaves on wounds while reciting charms could draw out infection or evil spirits. Others believed that trampling the plant insulted its spirit, which might lead to bad weather or poor health. It was long associated with Mars in astrological herbalism, linking it to blood, war, and healing.

Chicken of the Woods

Name - common name/s and Latin name

- Chicken of the Woods

- Sulphur Shelf

- Laetiporus

- Laetiporus Sulphureus

Origin

Chicken of the Woods is native to Europe and North America and is widespread across the UK. It typically grows on deciduous trees, especially oak, cherry, and beech, but can also appear on conifers. It thrives in temperate woodland environments and is commonly found from late spring through autumn.

Summary

This distinctive bracket fungus is known for its bright yellow to orange shelf-like growths and meaty texture. It appears as overlapping tiers on tree trunks or stumps, often growing in large, vibrant clusters. Its name comes from its fibrous, tender flesh, which is said to resemble the texture of cooked chicken.

Chicken of the Woods tends to emerge after warm rains, with fruiting bodies developing rapidly. It is typically seen between May and October in the UK.

Where to find Chicken of the Wood

Often found growing on living or dead broadleaf trees such as oak, chestnut, yew, cherry, and willow. It can appear high up on trunks or low near the base. Woodland edges, parklands, and old tree-lined paths are common habitats. It prefers older or decaying wood and is frequently found in the same locations annually.

How to Identify

Chicken of the Woods is unmistakable due to its vibrant colour and structure. The fruiting body forms thick, semi-circular brackets that grow in overlapping layers. The upper surface is smooth and ranges from bright yellow to orange, fading with age or sun exposure.

The underside is sulphur-yellow and covered in tiny pores, not gills. The texture is soft and moist when young, becoming brittle and chalky as it matures. When cut, it reveals a pale yellow interior that may exude moisture.

Caution: Avoid specimens growing on yew, eucalyptus, or cedar, as these may absorb compounds that cause digestive upset.

Sensory Information

When fresh, it has a slightly sour, mushroomy smell and a mild taste. Its texture is dense and fibrous, with a chewiness that resembles chicken breast when cooked. The colour ranges from lemon yellow to deep orange, with the flesh remaining pale inside.

How to Use

Harvest young, tender brackets using a knife. Only the outer, softer edges are typically used for cooking, as older parts become tough and woody.

Chicken of the Woods is best when sautéed or fried and can be battered, grilled, or shredded into strips. It pairs well with bold flavours like garlic, herbs, or smoky spices. It is often used in vegan and vegetarian dishes as a meat substitute. Avoid consuming large quantities on the first try, as some people may have mild intolerances.

Do not eat raw, as it can cause stomach upset. Cook thoroughly before consumption.

Non food and drink uses

Occasionally used in natural dyeing, producing bright yellows and oranges on wool or fabric. The dense fruiting body also contributes to forest nutrient cycles as it breaks down wood.

Cultural References & History

While not as historically documented as other wild mushrooms, Chicken of the Woods has become increasingly popular among foragers and chefs due to its culinary versatility. Its bright appearance and culinary use have made it a favourite topic in modern foraging books and courses.

Mythology

Though not strongly tied to ancient folklore, its sudden appearance on trees was traditionally seen as a sign of wood decay. In modern mushroom lore, it is sometimes affectionately dubbed “the vegetarian’s chicken” and admired for its bold visual impact in the forest.

Chanterelle

Name - common name/s and Latin name

- Chanterelle

- Golden Chanterelle

- Girolle (French)

- Cantharellus Cibarius

Origin

The Chanterelle is native to Europe and North America, with Cantharellus cibarius widespread in temperate forests across the UK, mainland Europe, and parts of North America. It forms symbiotic (mycorrhizal) relationships with a variety of trees and has been collected for centuries in culinary traditions, especially in Scandinavia, France, and Eastern Europe.

Summary

The Chanterelle is a fleshy, trumpet-shaped mushroom that typically fruits from midsummer to early autumn, depending on rainfall and humidity. Its striking golden-yellow to orange colour, apricot-like aroma, and wavy-edged cap make it one of the most sought-after wild mushrooms.

Chanterelles are slow-growing and often reappear in the same woodland patches year after year. Their fruiting is dependent on specific conditions, often following warm summer rains, and they are usually found scattered across the forest floor rather than in dense clusters.

Where to find Chanterelles

Chanterelles grow in broadleaf and mixed woodlands, often near beech, birch, oak, and Scots pine. They prefer mossy, well-drained, slightly acidic soils and thrive in undisturbed, shaded forest environments. In the UK, they are most commonly found in upland woodlands and ancient forest habitats.

How to Identify

Chanterelles have a convex to funnel-shaped cap with wavy, irregular edges. The cap surface is smooth and dry, and the colour varies from pale yellow to rich golden orange.

One of their key identifiers is the underside of the cap: instead of gills, Chanterelles have blunt, forked ridges (called false gills) that run down the stem. These ridges are shallow and cannot be easily separated from the flesh.

The stem is solid, not hollow, and typically the same colour or slightly paler than the cap. The flesh is firm and white inside. Chanterelles emit a fruity aroma, often compared to apricots or stone fruit.

Caution: Do not confuse with the False Chanterelle (Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca), which has darker orange gills and softer texture, or the toxic Jack-o'-Lantern (Omphalotus illudens), which has true gills and grows in dense clusters on wood.

Sensory Information

Fresh Chanterelles have a sweet, fruity aroma reminiscent of apricots. Their flavour is mild, nutty, and slightly peppery, intensifying with gentle cooking. The texture is dense and meaty when fresh, making them ideal for sautéing or slow cooking. Colour ranges from pale yellow to deep egg-yolk orange.

How to Use

Chanterelles should be carefully harvested using a knife to cut at the base, avoiding disturbance of the mycelium. Clean gently with a soft brush to remove debris; avoid soaking in water as they absorb moisture readily.

They are best sautéed in butter or oil, used in cream sauces, risottos, pasta dishes, or paired with eggs. Their subtle flavour is enhanced with minimal seasoning. Chanterelles can also be dried, though this may mellow their aroma. When rehydrated, they can be added to soups or stews. Pickled chanterelles are a traditional method of preservation in parts of Eastern Europe.

Non food and drink uses

Chanterelles are occasionally used in natural dyeing to create yellow or gold tones, though this is less common. They are not widely used outside of culinary contexts.

Cultural References & History

Highly prized in European cuisine, particularly in French and Scandinavian traditions, Chanterelles have long been considered a delicacy. In Sweden and Finland, they are frequently preserved in butter or cream and stored for winter use. French markets often feature fresh girolles during the late summer and early autumn, and they are celebrated in local foraging festivals.

Mythology

Although not prominent in ancient myths, Chanterelles (like many forest fungi) have been loosely associated with fairies and forest spirits. In folklore, their sudden appearance after rain added to the mystique of mushrooms in general, which were often believed to grow in enchanted glades or "fairy woods."

Penny Bun

Name - common name/s and Latin name

- Penny Bun

- Cep

- Porcini

- Steinpilz (German)

- King Bolete

- Boletus Edulis

Origin

The Penny Bun is native to Europe, Asia, and North America. It is common in temperate woodlands across the UK, mainland Europe, and parts of North America. It thrives in deciduous and coniferous forests, forming symbiotic (mycorrhizal) relationships with trees such as oak, beech, birch, and pine.

Summary

The Penny Bun is a large, fleshy, and distinctive mushroom that appears from late summer into autumn, depending on climate and rainfall. Its fruiting season typically runs from July to October in the UK. Younger specimens are firm and round, becoming flatter and softer with age.

The cap starts pale and becomes a rich, golden brown, reminiscent of a crusty bread roll—hence the name "Penny Bun." As the season progresses, older mushrooms may become spongy or waterlogged, and prone to maggot infestation.

Where to find Summer Truffle

Penny Buns grow in a wide range of woodland habitats, especially in association with mature broadleaf trees like oak, beech, and birch, but also with conifers such as pine and spruce. Look for them growing singly or in small groups on the forest floor, often near tree roots.

How to Identify

The Penny Bun has a large, rounded cap (up to 30 cm across) that is pale to dark brown, with a smooth, slightly sticky surface when damp. Its thick stem (stipe) is bulbous, pale or tan, and often features a fine white net-like pattern (reticulation) near the top.

Underneath the cap are pale pores rather than gills; these pores are white when young, turning yellow-green with age. The flesh is thick, white, and remains unchanging when cut (unlike some toxic lookalikes).

Beware of confusing it with bitter boletes (Tylopilus felleus) or poisonous boletes, which can have red or orange pores and may stain blue when cut or bruised.

Sensory Information

The Penny Bun has a mild, nutty, and pleasant mushroom aroma. Its taste is rich, earthy, and savory, with a hint of sweetness when cooked. The cap is chestnut brown to tan; the stem is pale cream to light brown with a distinctive net-like pattern.

The white flesh stays firm and does not discolor when cut. Young specimens are best for cooking due to their dense texture.

How to Use

Harvest Penny Buns by slicing them at the base, leaving the underground mycelium intact to encourage regrowth. Check for insect holes or soft spots, as older mushrooms are often infested.

They can be eaten fresh, dried, or preserved. Drying intensifies their flavor, making them ideal for soups, sauces, risottos, and pasta. Dried Penny Buns can be rehydrated and used in stocks or ground into powder for seasoning.

Classic recipes include porcini risotto, mushroom soup, and sautéed Penny Buns with garlic and herbs. In Italy, dried "Porcini" are a valued pantry staple.

Non food and drink uses

Penny Buns are primarily culinary mushrooms and are not commonly used for non-food purposes. However, their spores and decaying bodies contribute to forest soil health.

Cultural References & History

Known as "Cèpe" in France and "Porcini" in Italy, the Penny Bun is a beloved wild food in European cuisine, featured in traditional dishes and local markets. In German-speaking countries, the “Steinpilz” (stone mushroom) is highly prized.

Historically, these mushrooms have been gathered for centuries and traded in dried form across Europe. In folklore, they were sometimes thought to mark the presence of fairies or woodland spirits due to their sudden, mysterious appearance.

Mythology

While the Penny Bun itself is not deeply embedded in myth, mushrooms in general have long held magical associations in European folklore. "Fairy rings" of mushrooms were said to be dancing circles of fairies, and some believed that gathering mushrooms improperly could offend woodland spirits.

Summer Truffle

Name - common name/s and Latin name

- Summer Truffle

- Burgundy Truffle

- Black Summer Truffle

- Tuber Aestivum

Origin

The Summer Truffle is native to much of Europe, especially southern and central regions including France, Italy, Spain, and parts of the UK. It typically grows in calcareous (chalky or limestone) soils in warm, temperate climates, often forming symbiotic (mycorrhizal) relationships with the roots of certain trees.

Summary

The Summer Truffle is a subterranean fungus (hypogeous), forming rounded, knobbly, rough-textured fruiting bodies underground. They are usually harvested from late Spring through to early Autumn, with peak season in Summer. The outer skin, or peridium, is dark brown to nearly black with prominent polygonal warts. The inner flesh (gleba) is pale cream to light brown with white marbling.

As the season progresses, the aroma and flavour of the truffle intensifies, although they are generally milder than the winter truffle (Tuber melanosporum). In late summer and early autumn, the Burgundy Truffle (Tuber uncinatum), a closely related species or variety, appears and is sometimes sold under the same name.

Where to find Summer Truffle

Summer Truffles grow in symbiosis with the roots of certain deciduous trees, particularly oak, hazel, hornbeam, and beech. They are found buried just below the surface in light, well-drained, calcareous soils in woodlands, forest edges, and sometimes even in truffle orchards specifically planted for cultivation.

How to Identify

Summer Truffles are small to medium-sized (2–10 cm) rounded tubers with a rough, warty exterior that is black or dark brown. When sliced open, the interior shows a pale cream to beige color veined with white marbling. The scent is nutty, earthy, and slightly mushroom-like—much lighter than the strong aroma of winter truffles.

Care should be taken to distinguish them from other truffle species, some of which are not edible or have inferior taste.

Sensory Information

The Summer Truffle has a gentle, nutty, and slightly sweet aroma with earthy and mushroom undertones. Its flavour is mild, with hints of hazelnut, garlic, and earth. The exterior is blackish-brown with pronounced warts, while the interior is cream to light coffee-brown with delicate white veining.

How to Use

Truffles are traditionally located with the help of trained dogs or pigs, which can detect their scent underground. Once unearthed, they should be gently brushed to remove soil; washing is only done sparingly to preserve flavour. They must be consumed fresh or stored carefully in an airtight container, often with rice or eggs to absorb their aroma.

Summer Truffles are best used fresh, thinly shaved over pasta, risotto, eggs, or salads. Because their aroma is milder than other truffles, they are less suitable for long cooking and are usually added at the end of a dish or used raw. They can also be infused into oils, but should not be overly heated as this diminishes their fragrance.

Popular recipes include truffle butter, fresh truffle pasta, and truffle-infused scrambled eggs.

Non food and drink uses

Summer Truffles are not known for non-culinary use. Their value and use are almost entirely gastronomic and cultural.

Cultural References & History

Truffles have been prized since ancient times in Mediterranean cuisine and culture, referenced by Greeks and Romans as luxury foods believed to possess aphrodisiac and mystical powers. The Summer Truffle, while less valued than the Winter or White truffles, was traditionally gathered by European peasants and sold in local markets as a delicacy of the countryside.

The French and Italian culinary traditions both revere this truffle for its subtle enhancement of simple, rustic dishes like omelettes, pastas, and fresh cheese.

Mythology

In classical antiquity, truffles were thought to be formed by lightning striking the earth—a gift from the gods. The Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder considered truffles a natural marvel, though their true nature was a mystery until the discovery of their fungal origins centuries later.

Truffles in general (including Summer Truffles) have been shrouded in mystique, believed to bring fortune and fertility, and have long inspired myths about their origin and supposed magical properties.

Sugar Kelp

Name - common name/s and Latin name

- Sugar Kelp

- Sweet Kelp

- Sea Belt

- Kombu Royale

- Saccharina Latissima

Origin

Sugar kelp is native to the cold, temperate waters of the North Atlantic and North Pacific Oceans. It is commonly found along the coasts of Northern Europe (including the British Isles, Norway, and Iceland), as well as North America, especially along the Atlantic coasts of Canada and the United States.

Summary

Sugar kelp is a large brown seaweed that can grow up to 4–5 meters in length. Its broad, strap-like fronds feature a distinctive crinkled or wavy appearance along the edges. Growth is most vigorous in Spring and Summer, making these the ideal seasons for harvesting. In Winter, growth slows, and older fronds may appear tattered or broken.

Sugar kelp stores sugars in its tissues as a protective response to cold stress, which gives it its sweet reputation. These sugars increase slightly during colder months, contributing to its "sugar" name.

Where to find Sugar Kelp

Sugar kelp grows in subtidal zones, typically from just below the low tide mark down to several meters deep. It attaches itself firmly to rocks or other hard surfaces in clean, nutrient-rich waters. It can be found along the coasts of Scotland, Ireland, Scandinavia, and North America’s Atlantic seaboard.

How to Identify

Sugar kelp has wide, golden-brown to dark brown fronds that are long, flat, and ribbon-like with crimped or wavy edges. The fronds are typically smooth and shiny when wet. A strong, tough central midrib runs the length of each frond, giving it structure. The plant is firmly attached to rocks via a small holdfast.

Sensory Information

Sugar kelp has a fresh, sea-like aroma, less intense than other seaweeds. Its taste is sweet and umami-rich, with a hint of natural sugar, especially when dried. The colour varies from golden brown to dark olive or deep brown depending on age and exposure. When dried, the fronds may develop a white, sugary bloom of natural salts and sugars on the surface.

How to Use

Sugar kelp is harvested by hand or sustainably cut from cultivated sea farms. Only the fronds are taken to allow the holdfast and stipe (stem) to regrow. After collecting, it is rinsed well in fresh water to remove grit, then dried or used fresh.

In cooking, sugar kelp is used similarly to Japanese kombu as a broth base for soups and stocks. It can be sliced and added to stir-fries, pickled, or used in salads after blanching. When dried and then rehydrated, sugar kelp becomes tender and slightly sweet. A simple use is as a seasoning: dried and ground sugar kelp can be sprinkled on dishes to add a salty, umami flavour.

Traditional recipes include kelp soup, kelp-wrapped fish, and fermented kelp condiments.

Non food and drink uses

Sugar kelp is valued for its use in cosmetics and skincare products for its mineral-rich extracts. It is also a potential source of biofuel and is being explored in biodegradable packaging materials. Historically, kelp species were burned to produce potash for soap and glass making. Some natural dyers use kelp to create subtle beige or greenish hues.

Cultural References & History

While not as prominent in traditional songs or poems as other plants, sugar kelp and other large kelps have been historically important for coastal communities in Europe and North America. In Scotland and Ireland, kelp burning for soda ash was a major industry in the 18th and 19th centuries. Kelp also played a role in Japan’s culinary history as a key ingredient in dashi broth.

In modern times, sugar kelp is experiencing renewed interest as a sustainable food and environmental resource, especially in sea farming for climate-friendly agriculture.

Mythology

In Norse and Celtic sea myths, kelp forests were thought to shelter sea creatures and spirits. Some tales spoke of "kelpie" water spirits (though unrelated in name to kelp) that haunted kelp-laden shores. Seaweeds in general were considered gifts of the ocean deities, providing both nourishment and protection from storms.

Dulse

Name - common name/s and Latin name

- Dulse

- Sea Lettuce Flakes (occasionally, though this can also refer to Ulva species)

- Palmaria Palmata

Origin

Dulse grows in the cold waters of the North Atlantic and parts of the Pacific. It is especially abundant along the coasts of Ireland, Scotland, Iceland, Canada (notably Newfoundland), and northern parts of the United States. It has been harvested for centuries in these regions as a food and as a medicinal plant.

Summary

Dulse is a red algae that grows attached to rocks or larger seaweeds in the lower intertidal and subtidal zones. It forms soft, flattened fronds that can reach lengths of up to 50 cm. The plant’s growth is most vigorous in Spring and Summer, with harvesting typically done in these warmer months when the fronds are fullest and richest in nutrients. In Winter, growth slows, and the fronds may appear darker and more brittle.

Where to find Dulse

Dulse is found on exposed rocky shorelines and in the subtidal zones of the North Atlantic. In the British Isles and Ireland, it is gathered by hand during low tide. In Canada, particularly Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, dulse has been traditionally gathered and dried for preservation.

How to Identify

Dulse has broad, reddish to purplish fronds with a distinctive flattened and leathery texture. The fronds are usually branched and may show ruffled or wavy edges. When wet, they are soft and flexible; when dried, they become crispy and brittle. Dulse can sometimes be confused with other red seaweeds, but its wider, fan-like, and often translucent blades help distinguish it.

Sensory Information

Dulse has a mild sea scent, less briney than other seaweeds. When eaten raw, it has a salty, slightly smoky flavor with a savoury, umami quality often compared to bacon when crisped. The color is a rich deep red to purple, turning darker when dried. When cooked or toasted, the taste becomes stronger and more savoury.

How to Use

Dulse is hand-harvested at low tide from clean coastal rocks, taking care not to strip the holdfast to allow regrowth. After collection, it is washed thoroughly in fresh water and usually dried in the sun or with gentle heat to preserve it.

It can be eaten raw, dried, toasted, or cooked. In Irish and Scottish traditions, dulse was chewed as a snack or rehydrated in soups and stews. Toasting or frying dulse until crisp is a popular modern use, providing a bacon-like flavour for vegan dishes. It can also be ground into flakes and used as a seasoning.

Popular recipes include dulse crisps, where the dried seaweed is toasted or lightly fried until crunchy, and dulse butter, where flakes are mixed into soft butter for use on bread or vegetables.

Non food and drink uses

Dulse has been used as a source of potash and iodine historically. In some traditional crafts, it has been included in natural fertiliser mixes. Though less common than other seaweeds for dyeing, its pigment can impart reddish or purplish hues when used carefully in natural dye processes.

Cultural References & History

Dulse has a long history in Irish, Scottish, and Icelandic diets, often eaten as a snack food, medicinal plant, or wartime ration. In Newfoundland, dulse was sold dried in markets and eaten as a salty treat. References to dulse occur in Irish and Scottish folklore as a healthful and sustaining food, particularly for coastal fishing communities.

Mythology

While not as steeped in direct myth as some other plants, seaweeds like dulse were associated with life-giving properties from the sea in Celtic and Norse traditions. In some stories, seaweed offerings were made to appease sea spirits or ensure safe passage, and plants like dulse were seen as a gift of sustenance from the ocean gods.

Carageen

Name - common name/s and Latin name

- Carrageen

- Carrageenan

- Irish Moss

- Sea Moss

- Chondrus Crispus

Origin

Carrageen is native to the cold waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. It is commonly found along the coastlines of Ireland, Scotland, parts of northern Europe, and the Atlantic coast of Canada. Its long history of use in these regions reflects its natural abundance in these cold, rocky shore environments.

Summary

Carrageen is a type of red seaweed with fan-shaped, branching fronds. Its appearance changes slightly with the seasons. In the spring and early summer, growth is at its peak, and the seaweed is thick and lush. During winter, the fronds may become thinner and less vibrant. The coloration of Carrageen ranges from deep reddish-purple to greenish-yellow, depending on environmental factors such as light exposure and water conditions.

Where to find Carrageen

This seaweed thrives in the intertidal zone of rocky seashores. It can be collected by hand during low tide from rocks along the coasts of Ireland, Scotland, and Atlantic Canada. When foraging, it is important to select clean, unpolluted areas to ensure the seaweed is safe for consumption.

How to Identify

Carrageen is easily recognised by its flat, fan-like fronds that branch out into cartilaginous, rubbery segments. The texture is firm but flexible, allowing the fronds to stretch slightly without breaking. Colors may vary from dark purple to reddish-brown or green, influenced by the plant's age and its environment. A mild, salty sea scent is also characteristic.

Sensory Information

Carrageen has a gentle briney smell reminiscent of the ocean. Its taste is slightly salty with a delicate, subtle marine flavour, free from bitterness. The seaweed’s colours range from rich purples and reds to lighter greens or yellows depending on growth conditions and exposure to light.

How to Use

Carrageen should be harvested by hand from clean, rocky shorelines during low tide. After collecting, rinse thoroughly in fresh water to remove sand, grit, and salt. Traditionally, Carrageen is boiled to release its natural gelling properties, which makes it an excellent thickener for soups, broths, and desserts.

A well-known recipe is Irish Carrageen Pudding, in which the seaweed is simmered in milk along with sugar and vanilla. After straining out the fronds, the liquid is chilled until it sets into a light, creamy dessert. Carrageenan extracted from this seaweed is also widely used in the commercial food industry as a natural stabilizer and thickener in products like ice cream and plant-based milks.

Non food and drink uses

Beyond culinary applications, Carrageen has been used as a thickening agent in cosmetics and pharmaceutical products. In textile crafts, it serves as a thickener for dyes, helping to create consistent colour application. Traditionally, it has also been employed in remedies for respiratory and digestive ailments.

Cultural References & History

Carrageen holds an important place in Irish cultural history. It was widely consumed during times of scarcity, such as the Irish famine, valued for its nutritional and medicinal properties. Folklore often praises the health-giving powers of this seaweed, and it has been regarded as a natural remedy to maintain strength and vitality, especially in coastal communities.

Mythology

In Celtic mythology, seaweeds like Carrageen were believed to have protective and healing powers. They were seen as gifts from the sea gods, meant to sustain and nourish the people living near the shore. Some traditions suggest that respectfully harvested seaweed brought good luck and prosperity.

Bog Myrtle

Name – common name/s and Latin name

- Bog Myrtle

- Sweet Gale

- Myrica Gale

Origin

Native to cool, temperate regions of northern and western Europe and North America. It is especially prevalent in the peat bogs and moorlands of Scotland, Ireland, and northern England.

Summary

A fragrant deciduous shrub that prefers acidic, wet ground. It grows to about 1 metre tall and is characterised by slender, aromatic leaves and small catkins. It was historically one of the primary ingredients in gruit - a herb mix used in brewing before hops.

Where to find Bog Myrtle

Thrives in acidic peat bogs, wet moorlands, and damp heathlands. Most abundant in Scotland and the west of Ireland.

How to Identify

Low, bushy shrub with slender, pointed leaves with a silvery underside. Brown catkins appear before the leaves in spring. Emits a sweet, spicy scent when crushed.

Sensory Information

Leaves are resinous, spicy, and warm-scented. The flavour is slightly bitter and aromatic with a peppery, balsamic undertone.

How to Use

Leaves are used to flavour ales and stews. Dried foliage may be used in herbal teas or infusions, though sparingly. Historically blended with other herbs in food preservation.

Non food and drink uses

Known for its insect-repelling properties. Used in bedding, clothing sachets, and traditional household fumigation.

Cultural References & History

Once central to traditional brewing practices in Celtic regions. Known as a symbol of purification and love.

Mythology

Used in rituals to attract a lover or purify spaces. In folklore, it was believed to encourage prophetic dreams and keep negative forces at bay.

Wood Avens

Name – common name/s and Latin name

- Wood Avens

- Herb Bennet

- Geum Urbanum

Origin

Native to much of Europe and western Asia. Common throughout the UK, especially in shaded and semi-shaded areas such as woodland edges and hedge banks.

Summary

Wood avens is a perennial herb in the rose family, forming leafy rosettes at the base with tall, branched flowering stems. It blooms from May to August, producing small, yellow, five-petalled flowers followed by burr-like seed heads.

Where to find Wood Avens

Common in woodland edges, urban greenspaces, damp gardens, hedge bottoms, and disturbed soils. Prefers humus-rich and semi-shaded environments.

How to Identify

Basal leaves are round-lobed, with larger end leaflets. The flower resembles a small yellow buttercup. Seed heads develop into reddish burrs with hooked tips that cling to animal fur or clothing. The roots smell of cloves when dug up.

Sensory Information

Root aroma is spicy and clove-like, due to the presence of eugenol. Flavour is similarly warming and aromatic.

How to Use

Roots can be dried and used to flavour drinks and broths. Historically added to ale and wines for aromatic depth. Not to be confused with similar species that lack scent.

Non food and drink uses:

Roots were once used in incense and as natural moth repellents. Occasionally used in floral bundles for scent.

Cultural References & History

Mentioned in medieval herbals as “Herb Bennet,” meaning “Blessed Herb.” Thought to symbolise divine protection.

Mythology

In folklore, it was believed to repel evil spirits and wild beasts. Roots were worn for protection and planted near dwellings to bless the household.

Juniper

Name – common name/s and Latin name

- Juniper

- Juniperus Communis

Origin

Juniper is a native evergreen found throughout the Northern Hemisphere, from North America to Europe and parts of Asia. In Britain, it is one of the few native conifers and has a long history of cultural and culinary use.

Summary

Juniper is a slow-growing, evergreen shrub or small tree with needle-like leaves and berry-like cones, often called “juniper berries.” These take around 2–3 years to ripen, turning from green to blue-black. The shrub provides food and shelter for birds and insects and thrives in exposed, rocky places.

Where to find Juniper

Prefers dry, calcareous grasslands, heathlands, scrubby slopes, and open woodland. It is found across upland Britain, particularly in the Scottish Highlands, Cumbria, and Yorkshire Dales.

How to Identify

Needles grow in whorls of three and are sharp and prickly. The fruit starts green and matures to a deep purple-black with a waxy bloom. The plant has a distinctive, aromatic smell when the needles or berries are crushed.

Sensory Information

The scent is strong, resinous, and piney with citrus tones. The flavour of ripe berries is peppery, slightly sweet, and highly aromatic.

How to Use

Ripe berries are used to flavour game meats, sauces, pickles, and are essential in gin making. They can be dried or used fresh. Young green berries are not typically used. A small amount goes a long way due to its potency. Juniper is a protected plant under national legislation and site-specific designation in the UK.

Non food and drink uses

Wood is aromatic and traditionally used for incense, fumigation, and woodturning. Twigs were used in ceremonial fires and cleansing rituals.

Cultural References & History

Juniper has been used since antiquity for food preservation, spiritual purification, and even protection from pestilence. In medieval Europe, branches were hung in doorways to ward off evil.

Mythology

Considered sacred to Norse gods and often linked to Thor. In Highland traditions, burning juniper was part of house-cleansing rituals. Its presence was said to protect dwellings and promote healing.

Sweet Cicely

Name – common name/s and Latin name

- Sweet Cicely

- Myrrhis Odorata

Origin

Sweet cicely is native to Central and Southern Europe and has become naturalised in the British Isles, especially in northern and western parts. It favours cool, moist, and lightly shaded environments.

Summary

A hardy perennial of the carrot family, sweet cicely has bright green, feathery leaves and tall stems bearing large umbels of small white flowers from April to June. It grows up to 1 metre tall and often begins to flower before many other umbellifers. Its distinctive aniseed scent sets it apart from similar plants.

Where to find Sweet Cicely

It often grows near old settlements, farmyards, roadsides, damp pastures, hedgerows, and shaded woodland margins. In some regions, it escapes from gardens and becomes well established in the wild.

How to Identify

Feathery, fern-like leaves with white blotches at the base. The plant has hollow, grooved stems and dark brown, curved seeds with longitudinal ridges. It is one of the earliest-flowering umbellifers.

Sensory Information

Both the leaves and seeds have a pronounced sweet, aniseed or liquorice aroma. The flavour is fresh and slightly sugary, making it a natural sweetener.

How to Use

Traditionally used to sweeten stewed fruits like rhubarb or gooseberries. Leaves, stems, and seeds are edible. Young roots can be roasted. It is a culinary herb valued for both its flavour and digestive properties.

Non food and drink uses

Employed in aromatic sachets and historically in brewing as a flavouring herb. Sometimes cultivated as a fragrant border plant.

Cultural References & History

Sweet cicely was prized in monastic herb gardens and used widely before the arrival of cane sugar in Europe. Its name reflects its pleasant scent and taste.

Mythology

Symbolic of maternal protection and sweetness, it was associated with gentleness and care in northern European herbal folklore.

Wild Angelica

Name – common name/s and Latin name

- Wild Angelica

- Angelica Sylvestris

Origin

Native to Europe and parts of Asia, wild angelica is commonly found across the UK and other temperate regions. It thrives in damp environments and is a common sight in wet meadows, stream banks, and woodland clearings.

Summary:

Wild angelica is a tall, biennial or short-lived perennial of the carrot family. It produces a rosette of leaves in its first year, and in the second year sends up tall, hollow stems with umbels of pinkish or purplish-white flowers. The plant typically flowers from July to September.

Where to find Wild Angelica

Found in damp ground - marshes, fens, wet woodlands, ditches, and riversides. It thrives in moist soils with partial sunlight.

How to Identify

Sturdy, hollow, purple-tinged stems reaching up to 2 meters tall. Leaves are large, bipinnate and toothed. Umbels of flowers have 20–40 rays and are tinged pale purple or white. The scent is aromatic and somewhat musky.

Sensory Information

Aromatic, musky smell. The flavor is earthy and slightly sweet, with hints of aniseed.

How to Use

Young stems and leaf stalks can be blanched and used like celery, or candied. Seeds are used sparingly as a spice. Root can be dried and used for flavoring, though less commonly than garden ange

Non food and drink uses

Grown ornamentally and used in natural dyeing and fragrance blends.

Cultural References & History

Used in monastic herb gardens and often grown in physic gardens across Europe. Sometimes confused with garden angelica (Angelica archangelica).

Mythology

Believed to ward off evil and disease. In folklore, angelica was a protective plant, said to bloom on the day of Archangel Michael’s revelation.

Sweet Woodruff

Name – common name/s and Latin name

- Sweet Woodruff

- Galium odoratum

Origin

Native to Europe, North Africa, and western Asia. Common in shady, deciduous woodlands.

Summary

Sweet Woodruff is a low, spreading perennial with whorls of lanceolate leaves on square stems. In late spring, it bears loose umbels of small white, four-petaled flowers.

Where to find Sweet Woodruff

Whorls of 6–8 glossy leaves; square hairy stems; clusters of star-shaped white flowers; pungent hay-like scent when dried.

How to Identify

- Whorls of lance-shaped leaves

- Small white star-shaped flowers

- Square stems

- Hay-like scent when dried

Sensory Information

Fresh, green scent when picked. Dried plant develops sweet, vanilla-like aroma from coumarin.

How to Use

Used in spring punches (notably in Germany), cordials, or as a garnish. Traditionally dried for sachets and herbal decorations. Coumarin is toxic and products generally discontinued in EU, so only use under advice.

Non food and drink uses

Used in potpourri, bedding, and perfumes. Historically placed in linens to scent clothing. Also used as woodland groundcover in shade gardens; yields tan and gray-green dyes.

Cultural References & History

Popular in medieval herb gardens for scenting rooms and celebrating May Day.

Mythology

Linked with love and spring festivals. Also associated with sweetness, peace, and fidelity. It was thought to bring tranquil dreams and ward off nightmares.

Yarrow

Name – common name/s and Latin name

- Yarrow

- Achillea millefolium

Origin

Native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. Widespread in the UK.

Summary

Yarrow is a hardy perennial forming upright stems with feathery, bipinnate leaves. From June to September, it displays flat-topped clusters of white (sometimes pink) ray and disk florets.

Where to find Yarrow

Common in meadows, roadsides, pastures, and open grassy fields on well-drained soils.

How to Identify

Leaves are finely divided into thread-like segments; flower heads are corymbs of small composite blooms; stems may be slightly hairy and reddish at joints.

Sensory Information

Leaves emit a strong, sweet-herb aroma and a notably bitter, astringent taste. The flowers carry a mild honey note.

How to Use

Flowers and leaves can be brewed into an aromatic tea or used sparingly to flavour bitter beers and liqueurs. Fresh foliage was historically strewn as a pest repellent.

Non food and drink uses

Yarrow stalks make natural floral supports. It serves as a companion plant, repelling pests and attracting beneficial insects. Dried flower clusters produce yellow and green dyes.

Cultural References & History

Yarrow’s association with Achilles of Troy gave it the genus name; medieval battlefields often had yarrow strewn to staunch wounds. It appears in European divination and love rituals.

Mythology

Yarrow figures in Celtic and Norse lore as a sacred healing herb, used in protective charms and midsummer ceremonies.

Nettle

Name – common name/s and Latin name

- Nettle

- Stinging Nettle

- Urtica dioica

Origin

Native to Europe, Asia, and North Africa; now naturalized globally. Favors nitrogen-rich habitats.

Summary

Stinging Nettle is a perennial herb that emerges each spring from rhizomes. It grows 0.5–1.5 m tall, with opposite serrated leaves covered in stinging hairs. In summer, it bears drooping clusters of inconspicuous greenish flowers.

Where to find Nettle

Common in nitrogen-rich soils, near old buildings, along field edges, and woodland borders.

How to Identify

Opposite, ovate-to-lanceolate leaves with serrated margins; hollow stems and leaves densely covered in stinging trichomes; hanging panicles of tiny flowers.

Sensory Information

Fresh foliage delivers a sharp sting on contact. Once cooked or dried, nettles lose their sting and yield a mild, spinach-like flavour with an earthy green aroma.

How to Use

Wear gloves to harvest young top leaves in spring. Blanch or cook to remove sting. Use in soups, stews, teas, or as a spinach substitute.

Non food and drink uses

Nettle stems provide strong bast fibers used historically for textiles and cordage. Leaves can produce green dyes; infusion serves as a nutrient-rich plant feed and insect repellent.

Cultural References & History

Revered in medieval herbals, nettles were one of the Nine Sacred Herbs of Anglo-Saxon lore. They featured in rural traditions for strength and protection.

Mythology

Nettles were believed to offer protection and were placed in doorways or worn to guard against evil.

Hairy Bittercress

Name – common name/s and Latin name

- Hairy Bittercress

- Cardamine hirsuta

Origin

Native to Europe and Asia. Now common across much of the world, especially in disturbed soils and garden beds.

Summary

A small annual or biennial herb that germinates quickly and produces seeds explosively. Most noticeable in late winter to Spring, especially in mild climates. Bears tiny white, four-petaled flowers, followed by narrow seed pods that explosively eject seeds.

Where to find Hairy Bittercress

Common in gardens, lawns, paving cracks, pots, and other damp, disturbed ground in partial shade.

How to Identify

Look for the basal rosette of rounded leaflets with a larger terminal leaflet and fine hairs on the petioles; small white cross-shaped flowers; and long, narrow siliques that “pop” when ripe.

Sensory Information

Peppery, cress-like flavour. Fresh, green aroma.

How to Use

Harvest young leaves and flowering tops for a spicy salad green or garnish. Use sparingly to add a peppery note to soups, omelets, and sandwiches. Used similarly to watercress,

Non food and drink uses

Valued by early Spring pollinators; otherwise mainly regarded as a garden weed.

Cultural References & History

Known in Anglo-Saxon herbals as one of the Nine Sacred Herbs. Often referenced in literature for its explosive seed dispersal.

Mythology

In folk tradition, Hairy Bittercress symbolizes Spring renewal and resilience.

Ground Elder

Name – common name/s and Latin name

- Ground Elder

- Bishop’s Weed

- Aegopodium podagraria

Origin

Native to Europe and western Asia. It has naturalised in many temperate regions and is widespread across the UK.

Summary:

Ground Elder is a perennial herb that emerges in early Spring with erect, hollow, grooved stems bearing tri-foliate toothed leaves. In late Spring, it produces flat umbels of small white flowers. Extensive underground rhizomes allow it to form dense mats of foliage until die-back in Autumn.

Where to find Ground Elder

Common in hedgerows, woodland edges, old gardens, and shaded bank sides with fertile, moist soil.

How to Identify:

Foragers will note the distinctive whorls of three triangular, toothed leaflets, hollow ridged stems, and compound umbels of five-petaled white flowers in early summer. Rhizomes are cream-colored and slender.

Sensory Information

Young leaves have a mild parsley-like aroma and a slightly tangy, celery-like taste. Mature foliage becomes more bitter and fibrous.

How to Use

Harvest tender Spring shoots before flowering. Use raw in salads or blend into pesto. Cooked, the leaves can substitute for spinach in soups and stews. Avoid overharvesting to preserve the colony.

Non food and drink uses:

Ground Elder’s rapid ground-covering habit made it popular as an ornamental shade groundcover. Variegated cultivars appear in garden centres. Its rhizomes improve soil structure when composted.

Cultural References & History

Romans and medieval gardeners valued Ground Elder as a pot herb and folk remedy (its Latin name podagraria reflects its traditional use for gout). Monastic gardens cultivated it widely, giving rise to the name Bishop’s Weed.

Mythology

Not widely referenced in mythology, but often symbolises persistence and unwanted spread in folklore due to its invasive nature.

Scots Pine

Name – common name/s and Latin name

- Scots Pine

- Pinus Sylvestris

Origin

Native to Europe and Asia. It is the only native pine in the British Isles and forms iconic Caledonian forests.

Summary

A tall evergreen conifer with orange-red upper bark and paired blue-green needles. Produces male and female cones. Growth is year-round but slows in winter.

Where to find Scots Pine

Widespread in pockets of the Scottish Highlands, plantations, heathland, and sandy soils.

How to Identify

- Tall with straight trunk and flaking red-orange bark

- Paired needles (5–7 cm), twisted